The Hidden History Behind K-Pop Demon Hunters' Lovable Tiger

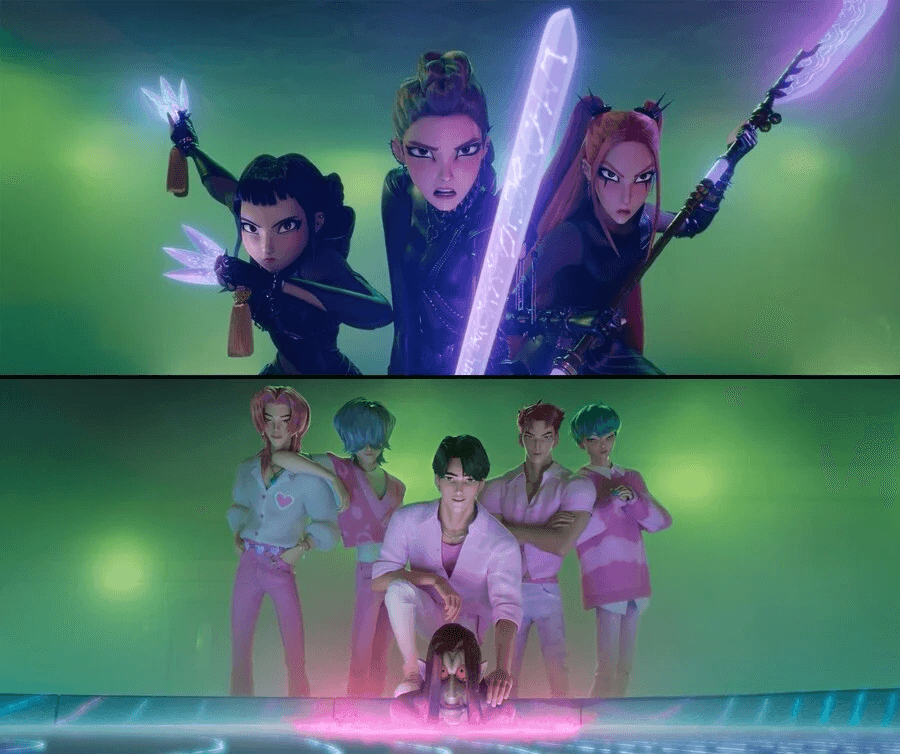

Ever wondered why that adorable tiger (호랑이/hoɾaŋi) in Netflix's K-Pop Demon Hunters acts more like a house cat than a fearsome predator? There's a fascinating 400-year-old Korean art tradition behind those lovably goofy expressions.

If you've been charmed by the tiger messenger in Netflix's latest animated hit "K-Pop Demon Hunters," you've unknowingly fallen in love with one of Korea's most subversive art forms. That bumbling but endearing tiger isn't just cute character design—it's the modern incarnation of a centuries-old Korean artistic rebellion that turned China's mighty tigers into lovable fools.

When Korea Said "No Thanks" to Intimidating Chinese Tigers

The story begins in 17th-century Korea, when Chinese tiger paintings were introduced through cultural exchange. These imported artworks, including works like "Child and Mother Tiger" (자모호도/jamohodo) and "Nursing Tiger" (유호도/yuhodo) from China's Yuan and Ming dynasties, were transmitted to Korea around the time of the Japanese invasions (1592). These paintings depicted tigers as they were meant to be seen: majestic, terrifying rulers of the natural world, symbols of imperial power and divine authority.

Korean artists took one look at these imposing beasts and thought, "You know what? Let's make them silly instead."

This wasn't accidental—it was artistic transformation disguised as humor.

The Art of Making Power Look Silly

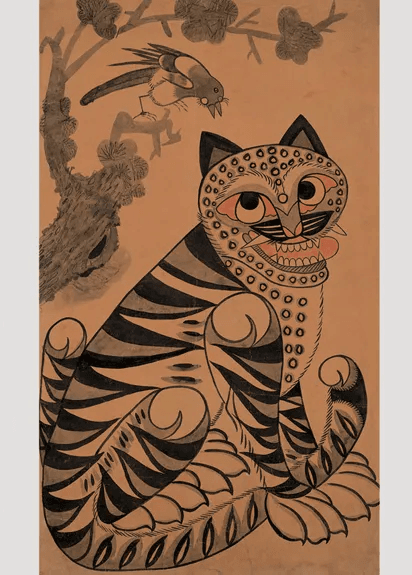

While Ming dynasty paintings depicted tigers as soft as mink blankets with meticulous detail, and pine trees and magpies were realistically expressed, Korean paintings gradually underwent a transformation starting in the 17th century. Three-dimensional expressions became flattened, and realistic backgrounds changed to expressionistic tendencies.

Korean folk artists deliberately exaggerated their tigers' features in the opposite direction from Chinese models. Big, startled eyes replaced piercing gazes. Awkward poses replaced graceful stances. Confused expressions replaced regal composure. The result? The beloved "babo-hoɾaŋi" (바보호랑이/silly tiger) that would become a cornerstone of Korean folk art (민화/minhwa).

But why would Korean artists want to make tigers look silly? The answer lies in the oppressive social hierarchy of Joseon-era Korea. Under the rigid Confucian class system, common people (서민/seomin) had little recourse against corrupt officials (탐관오리/tamgwan-ori) and aristocratic abuse.

Direct criticism could mean imprisonment or death, but art? Art could hide rebellion in plain sight.

The Genius Social Commentary Hidden in Humor

The "silly" tiger became a perfect metaphor for incompetent authority figures. When a Korean family hung a painting of a confused, bumbling tiger in their home, visitors would chuckle at the "harmless animal picture"—but everyone understood the real target of the satire. Those corrupt officials who strutted around like they owned the world? They were just as foolish as these painted tigers, all bluster and no substance.

Meanwhile, the magpie (까치/kkachi) perched cleverly above the confused tiger represented the common people's wisdom. Small but smart, the magpie looked down at the powerful predator with obvious superiority. The visual hierarchy was completely reversed: the tiny bird held the high ground while the mighty tiger stumbled around below, literally and figuratively beneath the clever bird.

The Art of Loving Resistance

What made this artistic rebellion so effective was how genuinely affectionate it was. Korean artists didn't create their silly tigers with cruel mockery—they drew them with a kind of fond exasperation, the way you might look at a beloved but hapless family member. The tigers were ridiculous, yes, but they were also somehow endearing in their confusion.

This emotional complexity is exactly what you see in K-Pop Demon Hunters' tiger character. The Netflix tiger acts like a domestic cat, gets easily distracted, and seems perpetually befuddled by the world around it. Yet when the moment demands it, this same "silly" tiger channels mysterious blue powers to help the demon hunters.

Just like the traditional paintings, the character manages to be both goofy and somehow protective at the same time.

Cultural Context: Tigers, Magpies, and Korean Values

The technical approach Korean artists used emphasized this duality. Instead of the fine, detailed brushwork (붓놀림/but-nolim) that Chinese masters employed, Korean folk painters (화가/hwaga) used bold, simple strokes that gave their tigers an almost cartoonish quality. Colors were brighter and more playful than their Chinese counterparts. Backgrounds were minimal, focusing attention on the central drama between the clever magpie and the bewildered tiger.

Pine branches (소나무 가지/sonamu gaji) became simple perches for wise magpies, while tigers lost all dignity in their portrayal. This wasn't just artistic style—it was cultural commentary wrapped in entertainment.

New Year Protection: Sehua(세화, 歲畵) Tradition

These magpie-tiger paintings were often created as sehua (세화/saehwa), New Year paintings hung at gates to ward off evil spirits from outside. Korean families would display these during New Year celebrations (새해 축하/saehae chukha), trusting that even "silly" tigers could serve as spiritual guardians (영적 수호자/yeongjeok suho-ja) protecting their homes from malevolent forces (악한 기운/akhan gi-un).

This dual function—entertainment and protection—made jakho-do paintings perfect for Korean folk beliefs (민간 신앙/mingan sin-ang). They could laugh at authority while still feeling spiritually protected.

From Feudal Satire to Global Animation

The genius of Korean "stupid tiger" art was that it functioned on multiple levels simultaneously. Children could enjoy the funny animal pictures. Adults could appreciate the political satire. Families could display them for spiritual protection while secretly reveling in their subversive message. And unlike direct political criticism, these paintings were essentially critic-proof—after all, they were just pictures of animals.

This multi-layered approach is exactly what makes K-Pop Demon Hunters so effective for modern global audiences. Kids see a cute, funny tiger companion. K-pop fans see an adorable sidekick. But viewers who understand the cultural context see something deeper: a centuries-old tradition of using humor to comment on power, authority, and social hierarchies.

Modern Echoes: From Hodori to Haechi

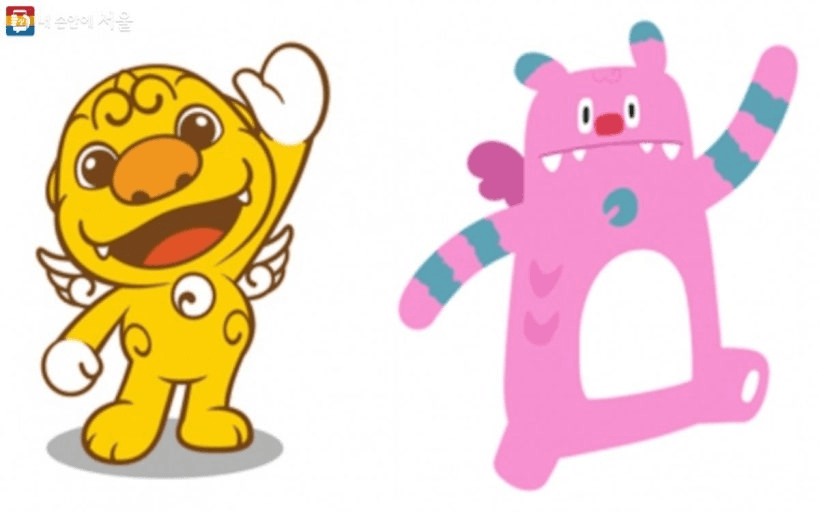

This tradition achieved global recognition when the tiger from Korean folk paintings was selected as the mascot for the 1988 Olympics. Hodori (호돌이), designed by Kim Hyun, brought the friendly, approachable Korean tiger to international audiences, proving the enduring appeal of Korea's "humanized" tiger tradition.

More recently, Seoul adopted Haechi (해치)—another traditional protective creature—as its official mascot, continuing Korea's tradition of using mythical animals as cultural ambassadors.

Why Silly Tigers Still Matter Today

The appeal of Korea's goofy tigers extends far beyond historical curiosity. In an era of global uncertainty and institutional distrust, there's something deeply satisfying about art that makes power look ridiculous while celebrating everyday wisdom. The same impulse that led Joseon-era farmers to chuckle at paintings of confused tigers resonates with modern audiences watching bumbling authority figures in everything from political satire to animated films.

K-Pop Demon Hunters proves that some artistic innovations are truly timeless. By grounding their fantasy world in authentic Korean cultural traditions, the creators tapped into something that transcends cultural boundaries: the universal human need to find humor in power and wisdom in unexpected places.

The next time you watch that adorable tiger stumble through its scenes in K-Pop Demon Hunters, remember: you're not just enjoying cute animation. You're experiencing the latest chapter in one of the world's most enduring artistic rebellions, where making tigers look silly became the smartest form of resistance imaginable.